A complete, feature-rich office suite, compatible with Microsoft documents, and totally free – such a thing can’t really exist, right? There must be a catch somewhere! Well, no. There’s no catch. No hidden costs. Nothing to be suspicious about. LibreOffice is indeed a complete suite of office tools, for zero cost, and it doesn’t make money through adverts or selling your data.

The reason it is free is simple: It’s made by a worldwide community, driven by volunteers, who are passionate about high-quality productivity software that’s free for everyone to use. LibreOffice’s goal is to bridge “digital divides,” making powerful tools available to everyone, regardless of their income, location, or language. Indeed, LibreOffice’s user interface has been translated into over 100 languages, making the software usable for many people in countries where other software vendors don’t have a presence.

Now, that’s not to say that all LibreOffice developers work on the software for purely philanthropic reasons. There are many “certified developers” who have customers using LibreOffice (such as companies or local government departments) and are paid to provide support packages, fix bugs, and implement new features. LibreOffice itself is (and will always be) completely free, but it still supports a viable commercial ecosystem around it.

If LibreOffice really is totally free (yes!) and compatible with Microsoft Office (indeed!), then why hasn’t the whole world moved over to it? Why is MS Office still around? There are various reasons for this, such as:

- Familiarity: Lots of people still aren’t aware that LibreOffice exists. The Document Foundation, the non-profit entity behind it, is working to improve this through marketing and events, but more needs to be done to spread the word.

- Resistance to change: Even when people discover LibreOffice, they’re often reticent to change, especially if they’ve already paid for another office suite. LibreOffice is familiar but looks and works slightly differently in places, and some more conservative users aren’t in a rush to switch over.

- Features: LibreOffice has the vast majority of features that everyday users need, and indeed even more than MS Office in some areas. But some specific workflows designed for MS Office require macros or special feature sets that don’t quite match up with LibreOffice. Still, with new LibreOffice releases arriving every six months, this changes quickly, and LibreOffice often takes the lead with rolling out new features that haven’t appeared in MS Office yet.

The LibreOffice suite includes several tools, including:

- Writer – the word processor (Figure 1)

- Calc – the spreadsheet (Figure 2)

- Impress – the presentation tool (Figure 3)

- Draw – for diagrams, flowcharts, leaflets, etc. (Figure 4)

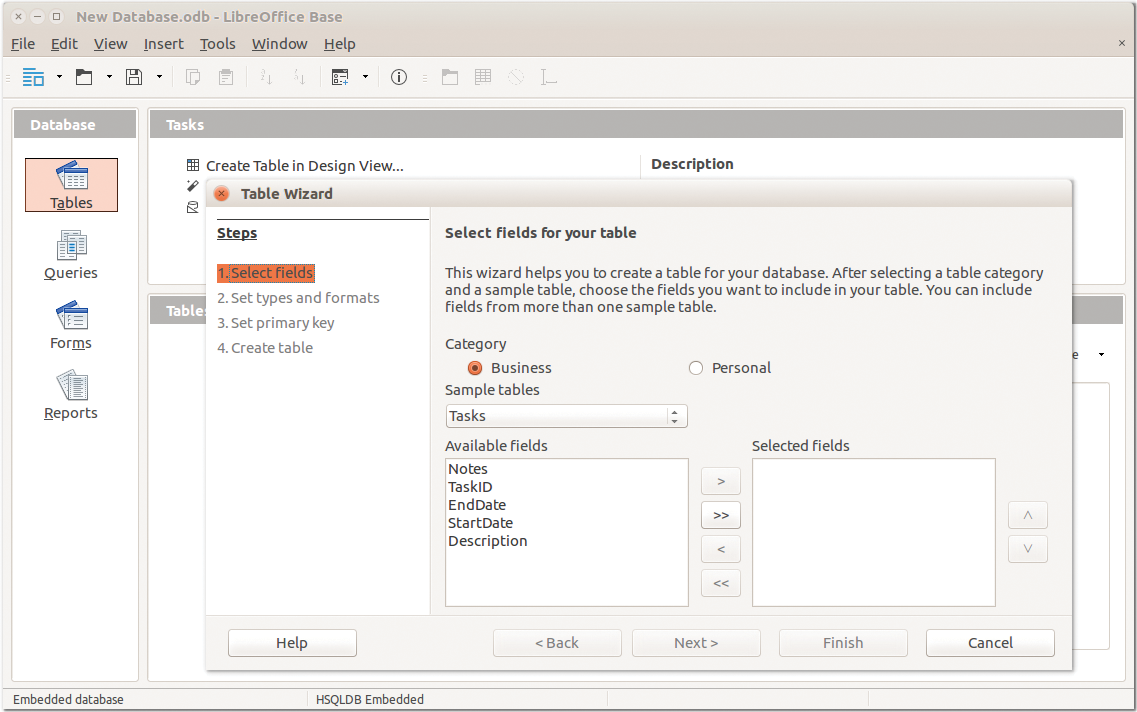

- Base – for databases (Figure 5)

- Math – to create formulae

Over the next few pages, I’ll provide a bit more background on LibreOffice and the community behind it, and I’ll show you how to install it. If you’re really itching to begin, skip ahead to the installation section – but don’t forget to come back here later and discover more about the suite! By learning about its history and background, you can help advocate for LibreOffice and spread the word to other potential users.

A Quick History

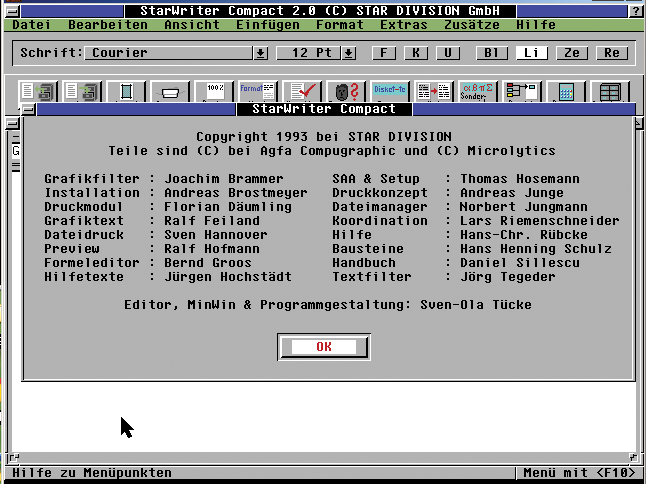

LibreOffice came to life in 2010, but its history actually goes back many years before that. Indeed, to explore the origins of what is today called LibreOffice, you have to go back to the 1980s, to a program called StarWriter (Figure 6). StarWriter was a commercial word processing application, created by German programmer Marco Börries, and it was made available for the 8-bit and 16-bit home computers at the time (such as the Amstrad CPC and PCs running MS-DOS). Over the next few years, Börries created a small company called Star Division to oversee the development of his program, adding additional tools such as a spreadsheet and drawing program. In 1992, StarOffice 1.0 for MS-DOS was released, followed two years later by StarOffice 2.0, which supported Windows and macOS.

StarOffice was relatively unknown compared to the mighty MS Office, but it was popular enough that new releases were made throughout the 1990s. Then something massive happened: Sun Microsystems, a major vendor of high-end servers and workstations, bought Star Division for a pretty impressive $73.5 million. The reasoning behind this? Many speculated that for Sun, which had over 20,000 employees at the time, buying Star Division was a cheaper way of equipping all its workers with an office suite than buying MS Office licenses. Others speculate that Sun was eager to get more involved in the home/personal computing space.

In any case, this suddenly meant that StarOffice had a much bigger company behind it – more resources and developers were available to work on it. In 2000, Sun released StarOffice 5.2 as a free download for personal use; the suite was also provided on many magazine cover discs. Microsoft suddenly had a lot more competition, and many people found StarOffice more than good enough for their daily tasks.

Then another major change occurred. The Free and Open Source Software movement was gaining a lot of traction at the time, promoting the benefits of software for which the source code (the human-readable recipe) is freely available. With open source programs, anyone can tinker “under the hood,” make improvements, and submit them back to the developers. Open source is a large collaborative effort, where the whole world can learn from it and make a difference, in contrast to closed-source programs like MS Office, where very few people can actually look inside it and improve it.

Sun was observing other open source projects gaining momentum, such as the GNU/Linux operating system and the Mozilla web browser (which lives on today in the form of Firefox, perhaps the most well-known open source app). In response, Sun decided to make the StarOffice code open for everyone to explore in a new project named OpenOffice.org. Yes, this meant that the world now had a fully free office suite – free as in zero cost, but free as in everyone could study its workings, make improvements, and share them.

After a couple of years of development, OpenOffice.org 1.0 was released in 2002. It wasn’t the prettiest of releases, with a few rough edges and less-than-stellar performance, but it was nevertheless a major milestone. Linux users in particular were happy to have a fully-featured, open source office suite that was provided by default with their operating system. A small update, OpenOffice.org 1.0, followed a year later, and then OpenOffice.org 2.0 arrived in 2005 with many performance improvements.

The Birth of ODF

Version 2.0 also used the OpenDocument Format (ODF) as its default format (Figure 7). Documents, spreadsheets, and drawings are stored on your computer as chunks of computer-readable data. At the time, Microsoft documents were stored in strange proprietary blobs of complicated, obfuscated data that was very difficult for other programs to read.

ODF was created as an alternative: The data was structured in an open and standardized way, built on XML, so that files saved in OpenOffice could easily be opened and understood by other programs as well. Users who save their work in ODF format can guarantee that they’ll be able to read the files in the future, by other tools, regardless of whatever happens to OpenOffice.org. (Years later, Microsoft created its own pseudo-standard called “OOXML,” and LibreOffice supports it too, while recent releases of MS Office support ODF.)

Over the following years, Sun and the OpenOffice.org community worked on new releases of the software, but there was ongoing concern that a single large company had a lot of sway in the project. Some ideas were brought up by the community, such as an independent foundation to oversee OpenOffice.org development, but nothing came of it.

Until 2009, that is. That’s when Sun was purchased by Oracle, a vendor of database software and other enterprise tools. There was immediate concern amongst the OpenOffice.org community, especially volunteers who’d contributed a lot to the project: What happens now? Will Oracle care about OpenOffice.org? Is Oracle a friend of free and open source software?

There was much discussion at the time, and then a bunch of community members made a big decision in 2010: It was finally time for a completely independent, non-profit entity to provide a future for the office suite. This entity was known as The Document Foundation (TDF), and the software was called LibreOffice.

LibreOffice began as a “fork” of the OpenOffice.org project. (Because OpenOffice.org was open source, anyone could take the source code and use it to start another project.) The vast majority of community members in OpenOffice.org joined the LibreOffice project straight away. So LibreOffice was the future of OpenOffice.org – it was built from the same source code, but with a new foundation behind it, a new brand, and new hopes for the future. OpenOffice.org continued as a much smaller project for a few years, but with relatively few updates compared to the rapidly-growing LibreOffice.

Since 2010, LibreOffice has gone from strength-to-strength: today, there are major deployments of the suite around the world, such as 500,000 installations in the French government. TDF estimates upwards of 100 million users of LibreOffice, and hundreds of members of the community meet every year for conferences, to work on new features and discuss the future of the software. Companies have emerged to provide support and additional features for the suite. And now you have a magazine about it, in your very hands!

So Let’s Install It!

You can download the full version of LibreOffice at any time from the LibreOffice website. The software is available for the three major desktop operating systems – Windows, macOS and Linux, although the themes and colors might vary depending on your system. The first step is to check out the system requirements:

- Windows: Microsoft Windows 7 SP1 with KB3063858 update, Windows 8, Windows Server 2012 through 2022, Windows 10, or 11

- Apple macOS (aka macOS X): macOS 10.12 (Sierra) or higher

- Linux: Linux kernel 3.10 or higher For smooth use, you’ll need at least 2GB of free hard drive space and 1GB of RAM – so any PC built in the last few years should be more than capable. For certain features, such as Base, Java is required, but you can use the suite without Java if you prefer.

Installing on Windows

- Get the

.msiinstallation file appropriate for your system (file name ending inWin_x64.msifor 64-bit systems orWin_x86.msifor 32-bit systems). Save the file onto your desktop, and then double-click it to start the installation process. - The installer wizard will appear, and you can simply keep clicking Next to accept the default options, which are perfectly fine for everyday use. (If a User Account Control dialog appears during the process, click Yes to continue the installation.)

- When the installation is complete, click Finish, and you can now delete the

.msifile from your desktop. Your shiny new LibreOffice installation is available in your program menu!

If you need any help, check out the installation instructions on the website, or if you get stuck, try asking the LibreOffice support community. When posting a message, remember to include lots of detail (LibreOffice version, operating system version, and any error messages you see).

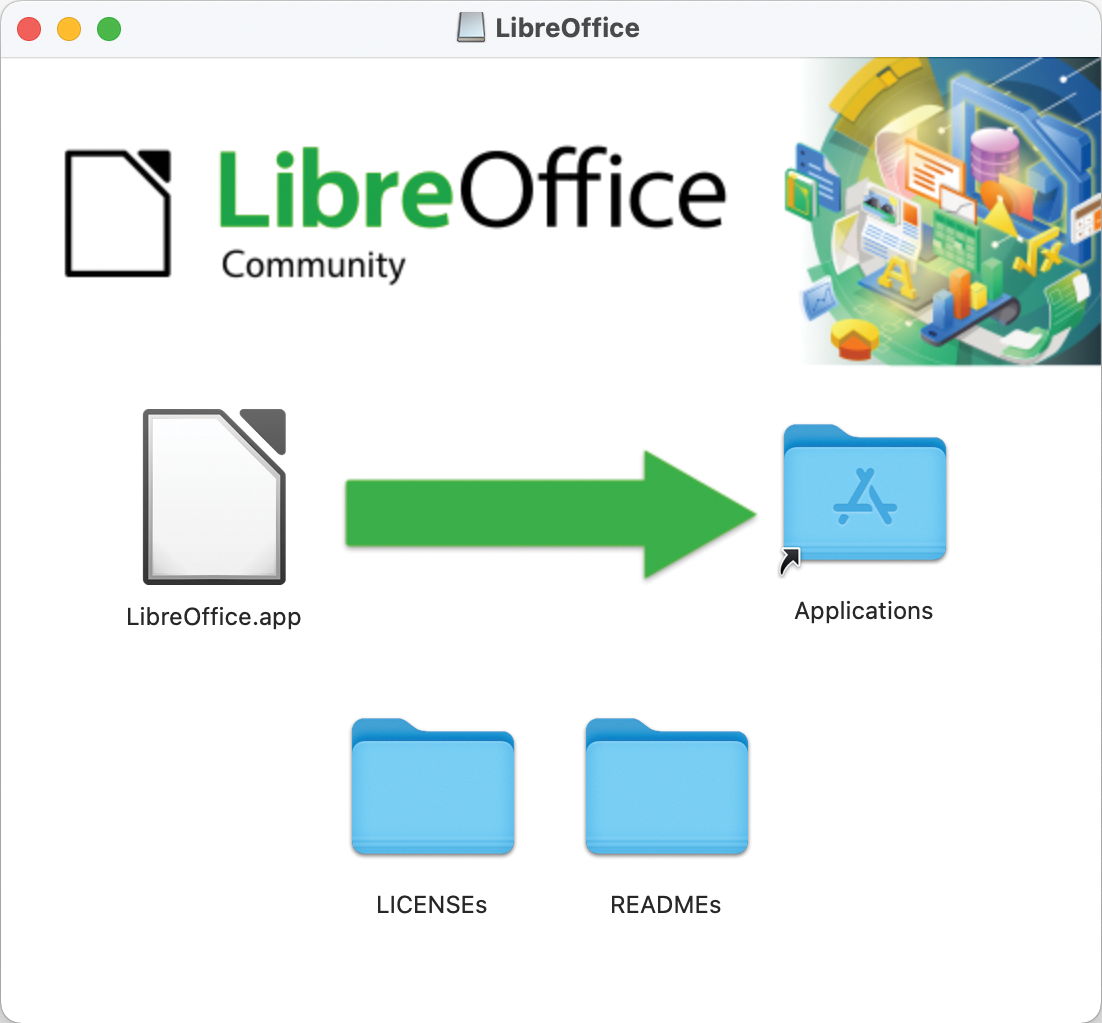

macOS

LibreOffice for macOS is provided in .dmg format, which is a virtual disk. Save the .dmg file to your desktop and double-click it to open. You’ll see a window like the one in Figure 8 – click and drag the LibreOffice icon into your Applications folder. (You may be required to enter your administrator password.) You can then launch the new software directly from the Applications folder (or drag the icon into your dock for easy access). You can also eject and delete the .dmg file.

.dmg disk image, and then click and drag the LibreOffice icon into your Applications folder.

Linux

The latest version of LibreOffice is available in .deb and RPM package formats on the DVD enclosed with this issue, but I generally recommend installing it directly from your Linux distribution’s package manager. This provides better integration with your distro and the possibility of automatic updates in the future. If you want to install from the latest .deb or RPM files though, follow the detailed steps on the wiki.

Conclusion

LibreOffice is a sophisticated office productivity suite that is available at no cost to Windows, macOS, and Linux users around the world. If you’re ready to start creating spreadsheets, presentations, and word processing documents without pouring your money into overpriced tools and complicated licensing scenarios, read on to discover the power and versatility of LibreOffice.

This article was originally published in LibreOffice Expert, a special issue that includes tutorials on all the core tools of the LibreOffice suite. Order your copy today!

Looking for a job?

Check out the latest job listings at Open Source JobHub.

Comments